- "...Even those with more resources do better by cooperating with those who have less. This insight needs further development, but suggests that the scope for beneficial cooperation is much greater than previously believed..."

Economic theory is great, but often needs adjustments for human unpredictability... like our altruistic or emotional reasons for doing things.

Ergodicity is a way of rethinking economic theory. Instead of plotting many possible futures from today, and picking the best one, Ergodicity looks at making decisions in a serial fashion, over time, to better model human economic behavior and influences.

This article is clearly written for someone with my less-than-informed economic skills and knowledge. But it links to the source materials that I expect several people here on Hubski have have distinct FEELINGS about.

I look forward to reading those analyses...

(NOTE: Please excuse the author for their subterfuge in the first paragraph. They are trying to make economics interesting to the layman, and it's a cheap stunt, but it worked on me. I read the whole thing.)

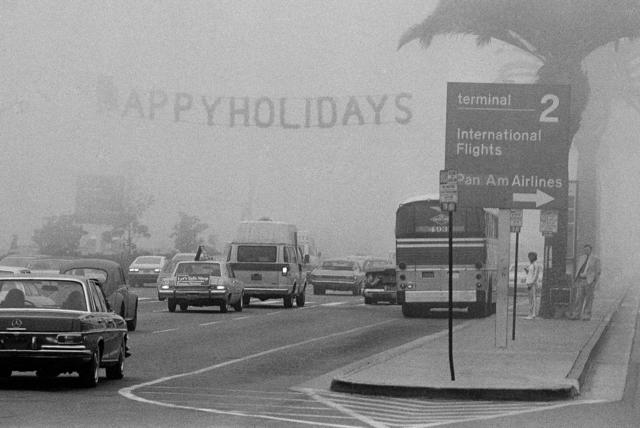

So, essentially, my understanding of economics (and the author's) are flawed, and economic theory does an excellent job of predicting outcomes that are not purely cost/benefit based. Which I don't believe, because I lived in LA in the 1970's. And, the EPA exists. It kinda sounds like I am being snide, but I'm not trying to. I just see Senators standing up with charts with no values on the X axis, and spouting reports from "Economists" that show something completely moronic. As a generic American, this is my full exposure to economics. I mean... I don't even balance a checkbook anymore...

As a skeptic of economics, who never broached 300-level economics, who did broach 300-level statistics, who did get an engineering degree and who has read at least two dozen pop economics books, I can say with much conviction and little credibility that the greatest difficulty economics faces, in every academic dispute about economics, is externality. I can use economic theory to argue for the EPA: they preserve the value of an asset against unfair exploitation. I can use it to argue against it: they inhibit the full utilization of resources by the stakeholders of the market. AllnI need to do is define "the market" to include or exclude people who breathe but don't pollute. The externalities of economics have gotten buried in the past forty years because Saint Milton argued that it was the job of business to exclude any stakeholders that were not direct economic components of the problem; he went as far as saying that businesses were required by their duty to their shareholders to extract as much value from the commons as possible, up to and including legal penalties, because any society that valued its environment (for example) would legislate sufficiently harsh penalties. No harsh penalties? Wrll then people are obviously fine with the Cuyahoga catching fire. The externalities of the political process weren't his problem, of course. He was an economist. Freakonomics is, down to the last example, a "gotcha!" approach to redefining externalities. Modern Monetary Theory is a redefinition of externalities. Universal Basic Income? A battle to redefine the externalities. So in the end, every economic battle, when you look at it from a systems point of view, is a battle over where to define the system of economics... Amd every article about "new" economics invariably reveals itself to be striking a blow to include some stakeholder or asset that has previously been judged an externality.

One only needs to look into history to find examples of this happening. It reminded me a lot of the creation of the Dutch water boards, which were originally created by groups of farmers in the 13th century realizing that if they built a large dike together instead of individual dikes, they could build stronger dikes for much less money per farmer. People band together if there's a clear long-term benefit - is that such a revolutionary insight?By pooling resources, those who do can be aided by others who don’t. Mathematically, it turns out that such pooling increases the grow rate of resources or wealth for all parties.

In economic theory, apparently it is. The difficulty is that economic theory has relied heavily on mathematical models, which - until recently - were not very good at calculation the very human parts of market interactions: emotions, altruism, collaboration, etc. Economists took a distinctly reductive approach to human behavior and said, basically, "If the person is going to gain monetarily from the interaction, then they will do it. Otherwise they will not." It was a very black and white treatment of something that is only black/white in psychopaths. Normal humans react with more nuance, and by evaluating other factors including altruistic inclinations. People band together if there's a clear long-term benefit - is that such a revolutionary insight?