whenever someone asks me to quote my favorite shakespeare, 'nothing in life became him like the leaving it' always springs to mind. lewis uses 'the dateless limit of thy dear exile' to illustrate the same thing. to me shakespeare was and is about the sentences and moments. the character studies always bored me, (and my high school english classmates, without doubt -- lewis isn't wrong that the approach ruins shakespeare for thousands of kids every year). "do you think hamlet was right to treat ophelia the way he did? how would you feel if you were ophelia? what motives do you think hamlet might have for his cruel dismissal? jesus #!$%$% christ i assume that stuff was dreamt up by some poor fool educator who was told he had to engage the kids with literature, and decided the self-insert route was the way to go. e.g. get the students to contrast hamlet/ophelia with their actual relationships, compare the reactions of the play's characters to the way they react to actual conversations. i suppose it could have worked, or maybe it did for some, but on the whole i pronounce it a failure perhaps i'm being unfair? what do you think lil

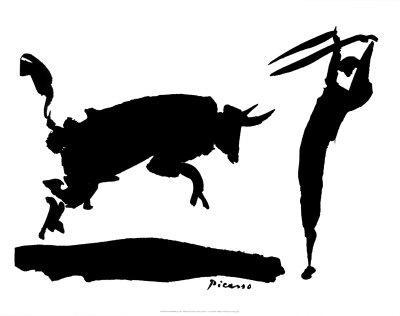

There's a fundamental assumption here that Shakespeare is literature. It's not. It's stage instructions. Shakespeare did not write his plays to be read. He wrote his sonnets to be read. He wrote his plays to be interpreted by actors who had to inhabit the role they were assigned and interact with the roles they were not. These actors together created a work of art for an audience that itself did not enjoy his works in splendid isolation; they enjoyed it together, in large crowds, simultaneously reacting to the jokes and the jabs and the puns and the references. Mercutio's lines were written for any actor playing Mercutio. They exist to give that actor enough of a sense of Mercutio that he can become Mercutio for the other players he shares the stage with so that together they can give Mercutio to the audience. When we read Mercutio we lack the multiple interlocutors between Shakespeare's words and Shakespeare's intended effect. This is why English teachers focus on the character effects of Shakespeare's plays rather than on the language of Shakespeare's plays; it's the character effects that are the immutable whole of a play, not the language. It's the character effects that we're supposed to see. It's the character effects that are most useful to teach because Shakespeare wasn't writing for us he was writing for people who would perform for us. I, too, had a shitty-ass time in English classes. I, too, hated the fuck out of most of the pedagogy I encountered. However it was abundantly clear to me that when we studied Shakespeare's language, we studied sonnets. When we studied Shakespeare's drama, we studied the plays. The kind that, with the fewest strokes, communicates hooves and haunches and hair in such a way that we not only see it, we see it anew. That's a bull, no doubt. The matador, on the other hand, is shockingly sparse. Yet we all have the context to know that the dagger-shaped blob on the right is a human and the stuff that isn't shown conveys the posture: the "ankles" sharpened to a knife-point suggesting raising himself to full height, the tiny blob beneath a precarious posture ready to strike, the arc backwards suggesting the full coil of attack or fear or both, the swords long and ill-defined yet still pointed precisely at the heart of the bull. When we look at Picasso we are informed by everything we know and everything we don't about bull-fighting. The black and white become an arena. I don't know about you, but I can smell that bullfight. Shakespeare's plays are not intended to be interpreted by us in this way. They're intended to be interpreted by a professional who lives with the writing, whose livelihood is dependent on someone else. Shakespeare didn't draw a bullfight. He wrote instructions on how to draw a bullfight. The genius of Shakespeare is he did such an exceptional job that us amateurs can draw that bullfight across five centuries, and debate the criticism of his instructions as if we're bullfighters. That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress when she walks treads on the ground. Shakespeare's sonnets are largely obvious.All of Shakespeare's plays are oblique. All of them. That they're as oblique as they are yet still studied (and enjoyed) across half a millennium says a lot.It is often cast in the teeth of the great critics that each in painting Hamlet has drawn a portrait of himself. How if they were right?

I can imagine a sketch so bad that one man thought it was an attempt at a horse and another thought it was an attempt at a donkey. But what kind of sketch would it have to be which looked like a very good horse to some, and like a very good donkey to others?

The only solution which occurs to me is that the critics’ delight in the play is not in fact due to the delineation of Hamlet’s character but to something else. If the picture which you take for a horse and I for a donkey, delights us both, it is probable that what we are both enjoying is the pure line, or the colouring, not the delineation of an animal.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know