I often wonder what logic (or lack thereof) is underpinning those who make a point to deny science. I'd also add GMOs to your list since there is some FUD surrounding them, although I think there are legitimate issues worthy of skepticism there as well. For skepticism of evolution, I kind of hand wave away as slightly more benign religious mumbo jumbo; it's an important topic for scientists to follow the evidence and get right, but if uneducated people want to believe in creation myths, I find that to be the least socially damaging out of all of them. Anti-vaccination people, I suspect, generally have a more-than-healthy skepticism of the pharmaceutical industry. To be honest, I don't immediately trust every new prescription drug, I don't think drug companies always have people's long-term health as their foremost concern, and I think there are plenty of conflicts of interest between doctors, drug-makers and regulators, but given a choice between accepting or rejecting modern medicine, vaccinations included, it seems fairly clear to me which is the lesser of two evils. I suspect there is also a latent fear among many people about issues of population control and eugenics, with vaccinations being vehicle for that. I don't know if anyone has seen the TV show Utopia, but it was all about that; if the worst predictions of global warming do come to pass, I suspect that humans, as a species, will need to have that kind of conversation about the carrying capacity of our planet. Global warming denial, though, I see as being from two groups. Some people deny it out of fear or ignorance; the thought of major coastal cities being rendered uninhabitable, food shortages and famines, ecological collapse, political unrest, revolutions and war, all the consequences certainly are frightening if you think that is what our children will face, and even more frightening if abrupt climate change causes them to occur in the, relatively speaking, near-term. The second group, I see as denying it out of greed or self-preservation; while they may recognize this as happening, they think it in their own best interest to preserve the economic status quo for as long as possible. I think it was from the COP 20 methane talk in Lima where one of the speakers mentioned a carbon bubble; once everyone recognizes what is happening, all the corporations that have massive holdings of carbon-based fuels will collapse in value. My personal belief is that parts of the US government are quite well aware of what's happening, what the worst-case scenarios could entail and are preparing for it. Much-ado is made about Jade Helm, but I think it's just bet hedging, preparing for a hostile domestic population in the event of water shortages, food shortages or unrest from weather-related events. I also suspect that many domestic surveillance tools are developed and maintained for this purpose as well. I find "conspiracy theories" surrounding global warming to be quite interesting. First, chemtrails, which is kind of a weird one, I think it's easy to dismiss the thought that planes are spraying this or that, but geoengineering as a possible counter to climate change is something I've heard suggested. It wouldn't seem out of the realm of possibilities for the US military to covertly test geoengineering technology. Secondly, weather control seems to be a popular theory among the more creative theorists; I've seen it suggested that the California drought is because of HAARP, or some other purposeful weather control technology (ignoring the irony that the California drought is the result of anthropogenic activity). I wonder where that kind of FUD comes from, and who aims to benefit from confusion like that. Lastly, I've seen some denialists point to the fact "global warming" used to be a common term, whereas now, many people use "climate change" to describe the phenomenon, and thus the scientists were wrong that the planet is warming and they're all backtracking. Of course, I always like to point out that language shift came from Frank Luntz, a propagandist employed by the second Bush, who thought "climate change" sounded less threatening than "global warming."

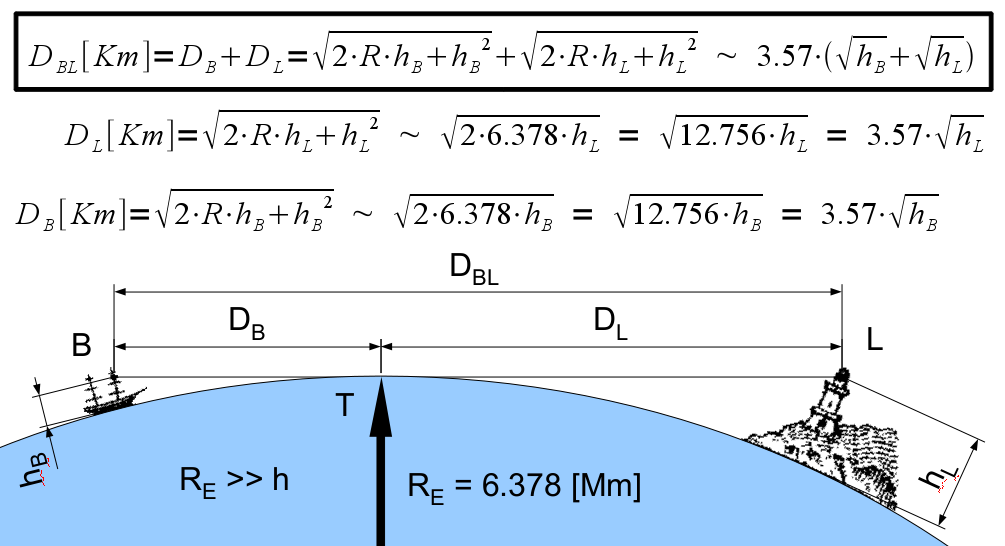

I always thought skepticism was at the very heart of science. “Trust what you have been told” is not a very satisfying argument. On a walk in the woods I am now making up, I met an ornery character outside a rustic cabin scrutinizing a ruler he was holding to the ground. “Hello, what are you up to?” I asked. “Hello. A strange old man passed through here and told me that the world is round, like an orange. I am trying to gather evidence to find out if it is true. It appears to me that my ruler approximately lines up with the ground.” “Oh! Well, the world is round, but you can’t tell by looking at a ruler. The ground is too uneven to demonstrate the curvature of the earth at that scale.” “I thought of that, so I checked the water in the pond and it is flat as a pancake. Like they taught me in school, water seeks its own level.” “Yes, but the curvature is very subtle. If you extend your ruler a very long way, and take very careful measurements, you might eventually notice a change of as much as a quarter of a millimeter. And if you go a very very long way, the change in water depth would be enough to drown a rat, or even submerge a city!” “A quarter of a millimeter? My ruler is only marked to the millimeter. How would I know it’s not measurement error?” “That’s the thing! There is a model which predicts exactly how much change to expect. You can work it all out in your cabin without going outside.” My smartphone had a shaky signal but after a while I was able to show the hermit the formula. After a pause, he said “So I would have to measure out over a hundred meters to detect a deviation of one millimeter. I’m gonna need a bigger pond.” “Don’t worry, other people have taken very careful measurements.” I started a Google search but the connection was too slow. “Anyway, the model is complex, but you can trust it, even if it is hard to experimentally verify. If I dropped a stone in your pond, you know that the water level would rise, even if you couldn’t measure the change, right? Scientists agree that this is a good model.” “And how do you know that?” “We took a survey! An online survey, you’ve heard of SurveyMonkey, right? Anyway, we asked over ten thousand expert scientists what they thought.” “And what did you find?” “Well, we learned that scientists have very good spam filters. But we still got responses from over three thousand scientists. And no fewer than 82% of them agreed that the curvature of the earth is the most important contributing factor explaining change in water level! Or, wait, maybe it was simply ‘a significant contributing factor,’ meaning ‘not definitely irrelevant,’ but that’s just semantics. There was a lot of agreement!” “Eighty-two percent still leaves some room for doubt.” “Yeah, we thought so too. So we threw out all the experts who were only mediocre experts, and counted the ones who were expert experts. That group was 95% in agreement. That’s science!” “It still sounds like there was some dissent.” “Not really. There were only 79 expert experts with bad spam filters, and only two of them said that the earth is flat. They are obviously crazy, so we didn’t count them. And only two of the rest disagreed, so that’s 75 out of 77. Since 97.4% is greater than 95%, we go with that number, for science. Promoting the consensus view is more important than being accurate in every little detail, don’t you think?”I often wonder what logic (or lack thereof) is underpinning those who make a point to deny science.

That is an interesting parable. Skepticism is an important quality and I suppose it comes down to a choice between trusting in your own experiences (however limited they may be) versus trusting in other people's experiences (however unreliable they may be). Everyone approaches that trade off differently. I think a big issue is that people place too much trust in the media's talking-heads, which at least in its mainstream corporate form, is little more than capitalistic and neoliberal economic propaganda. Like you point out, the real science is often inaccessible to a layman, which makes approaching that trade off even more challenging. Mass media propagation of some kind of "agreed-upon-consensus-by-people-smarter-than-me" pales in comparison to simple demonstrations of scientific principles, such that people can gain both expanded experiential understanding, as well as more trust in those researching the bigger reality beyond our five immediate corporeal senses. Unfortunately it's hard to find simple demonstrations of complex modern scientific principles. I expect that the scientists who study these things should endeavor to be very skeptical of accepted theories and be accurate in every little detail; however, I feel that myself, as a layman, must acknowledge it's counterproductive to be skeptical of every scientific theory and to only trust if I can find accuracy in every little detail. It does feel like a little bit of a "religion" when you look at it that way, but we all have to come to terms with the fact that reality is bigger than what our individual five physical senses can show us in our ephemeral lives, regardless of a spiritual or material world view. When some media-face says "Well, I'm skeptical of global warming because it was cold this week, and the sea level doesn't look any higher to me today than it did yesterday!" or "Well, I'm convinced of climate change because 99% of scientists agree x is causing y and z is our only hope of a solution!" I would approach both of those examples with extreme skepticism. Not enough people go beyond that to listen to the actual scientists, realizing that their theories are complex and fallible, but at the same time, profound in their potential ramifications for the future of our species. It's easy to believe in the theory of gravity, but considerably more difficult to believe in the theory of relativity. That isn't a big deal for civilization, unless belief in the theory of relativity was the only way to see our planet careening towards a black hole. I suppose while I do value skepticism, skepticism for skepticism's sake is deleterious if that act of questioning lacks the tools, evidence and cognition required to form a better understanding of reality. I can be skeptical of global warming, but would my skepticism have the potential to bring about a superior theory that can explain the changes scientists are observing? Probably not. I would value a climate scientist who is genuinely skeptical of global warming, because I sincerely hope that "the consensus" is wrong about what is causing these changes to our ecosystem, but for the average Joe-sixpack to simply cite "Skepticism!" as a reason by itself for disbelieving something seems counterproductive. On a more personal level, would you say that you're skeptical of the theory of anthropogenic global warming via carbon-dioxide emissions or methane feedback loops? While I do lend my belief to the scientists promulgating these theories, I am not closed to investigating opposing theories; as a layman, my scientific scrutiny is fairly weak but I have yet to come across any cohesive explanations that give me serious doubt about the prevailing theories on climate change.

I don't see it as such a dilemma. A big part of my own experience is reading about the evidence other people have gathered and created explanations for. Most of what I believe comes from what I have learned from others, not what I have personally verified. You believe that the world is round, like an orange, right? Could you demonstrate that belief to an intelligent, open-minded hermit? It might not be so simple. If I really didn't know the shape of the earth, it would be hard for me to determine it without outside help. My best argument is that a round earth fits into a consistent, plausible story that I have heard many times, which is also consistent with ideas like gravity, day and night, seasons, and the appearance and movement of the sun, moon and stars. It's not the only possible theory, it could be turtles. But the round earth theory fits the data better. I can also make personal observations of the tides, images from NASA and Felix Baumgartner, and ships on the horizon. I have seen the curved shadow of the Earth on the moon. How do I know it's the Earth's shadow? Someone told me. The same people who can predict an eclipse, even weeks in advance. That is good evidence that they understand something about whatever magic is behind the phenomenon. The early history of the Flat Earth Society is worth a look. There were arguments, a wager, a lawsuit, and most importantly: careful experiments made on the Old Bedford River, a six-mile straight canal. In 1904 Lady Blount hung a white sheet touching the surface of the river and had photographs taken with a telephoto lens from six miles away. By the Globularists' calculations the sheet should have been invisible, but it was visible in the widely-published photo, a great victory for the Zetetics. The photographer, a Globularist himself, wrote the Lady Thus the skeptics demonstrated that the world is not as simple as it sometimes appears. Today we have a better understanding of refraction, but the Zetitics persist. My skepticism makes me say "I am not sure it is true," not "I am sure it is not true." We see evidence of rising temperatures and increasing atmospheric carbon. It seems obtuse to ignore the industrial revolution as a likely source of the carbon, and a greenhouse effect as as a plausible cause of the warming. What that means for the future is hard to say with precision. I hope the controversy will lead to more careful research and a better understanding of the world. Having some doubt doesn't mean the best course is to stand by and wait, but I think it is reasonable to ask if there is enough evidence to justify costly interventions and how much benefit they will provide. Now that the subject is so politicized, BS detectors must be set to maximum sensitivity. I expect you have seen the "97%" consensus figure before. Were you at all surprised to see how the number was obtained? Have you noticed how easily and often the important distinction between "a significant cause of warming" (i.e. not definitely irrelevant) and "the cause of warming" is obscured? If the warming is actually explained by volcanoes instead of insufficient Prii, it doesn't mean we don't have a problem. But the responsible approach may be to give it some more time. I think climate science is in an early, uncertain stage, like the Victorians arguing over the river. The problem is difficult but the solutions are also very difficult and very expensive and far from infallible. The climate crisis also fits uncomfortably well into a very long history of gloomy predictions of doom which turned out to be completely contrary to fact. Maybe this time it's different.Skepticism is an important quality and I suppose it comes down to a choice between trusting in your own experiences (however limited they may be) versus trusting in other people's experiences (however unreliable they may be).

The issue was the relatively straightforward one of whether the Earth was flat (as the Zetetics held) or round (the Globularists). It's tempting from the comfort of a 21st century scientific perspective to laugh at the Zetetics, but we should perhaps be inclined to a little humility. The Zetetic philosophy was essentially one of 'proceeding by inquiry', which meant that any proof that the Earth was round would have to be the result of an experiment, not simply calculation.

I should not like to abandon the globular theory off-hand, but, as far as this particular test is concerned, I am prepared to maintain that (unless rays of light will travel in a curved path) these six miles of water present a level surface.

On a more personal level, would you say that you're skeptical of the theory of anthropogenic global warming via carbon-dioxide emissions or methane feedback loops?

I've heard of the flat-earthers, and I suppose it is an interesting examination of the value of skepticism. Reality is always more complex than a first or second glance can expose, and without questioning our theories and observations, we will never find truth. I guess framing it as a dilemma is misleading; perhaps a better way to look at it would be that some people have stronger preconceived views and seek out or reject evidence to reinforce those views, while others are more willing to let their views follow what evidence they encounter? I know that psychology can instinctively push our behavior into the former group, but I like to think myself, and many others, consciously try to avoid that, knowing the pitfalls which it entails. I think that is a good way of looking at it, and I would say I agree with that. Obviously I'm nowhere close to being a climate scientist, so if asked my opinion about it, the best I can do is basically parrot whatever seems plausible, or was said by the smartest people I think I've heard or read. And certainly, politicized issues require the highest degree of careful examination for propaganda. That is interesting about volcanoes, I hadn't really heard much about it, so I did some googling and pulled up a spate of articles from various sources, PopSci, Dec. 2012, Gizmag, Dec. 2012, Yale e360, May 2012, LiveScience, Jan. 2013. I also found a metabunk thread discussing, gathering and comparing geologic activity levels from various sources. I think you are certainly right about the earth being an incredibly complex system, so perhaps there is some sort of relationship there; most of the scientists talking about it seem to think the melting or freezing of glaciers and icecaps affect the pressure of subsurface magma, which would make sense, although I suppose it could be the other way around maybe? Pretty much all of the graphs on the metabunk thread indicate a fairly steady rate of geologic activity, in contrast with (comparatively) rapidly changing temperatures, so I guess I'm not sure if I feel particularly sold on the theory that increased volcanism is the driving factor of climate change, but I would hope that volcanologists are intensely studying any links there. The climate crisis also fits uncomfortably well into a very long history of gloomy predictions of doom which turned out to be completely contrary to fact. Maybe this time it's different. Well, I really hope the wait and see attitude turns out to be the right choice, because that feels like the path we're taking. I guess it is "cheaper" to just let humanity just ride out the changes as they occur, hoping they will be gradual enough that civilization does not collapse. I feel like the cheaper option today will be more expensive in the long run, but I suppose if there is one thing people have proven time and time again, we masters at passing on the price of our shortsightedness and lack of will to future generations. Unfortunately, considering my age, I worry my generation could bear a very heavy cost.My skepticism makes me say "I am not sure it is true," not "I am sure it is not true." We see evidence of rising temperatures and increasing atmospheric carbon. It seems obtuse to ignore the industrial revolution as a likely source of the carbon, and a greenhouse effect as as a plausible cause of the warming. What that means for the future is hard to say with precision. I hope the controversy will lead to more careful research and a better understanding of the world.

If the warming is actually explained by volcanoes instead of insufficient Prii, it doesn't mean we don't have a problem. But the responsible approach may be to give it some more time. I think climate science is in an early, uncertain stage, like the Victorians arguing over the river. The problem is difficult but the solutions are also very difficult and very expensive and far from infallible.