Shared most of my thoughts individually with a friend, and would rather not fully repeat them here (mostly out of laziness). That said I thought this was a pretty interesting read, OB, minus the fact that the author did not cite any of his sources and overall is not particularly constructive about his message.

I think that initially, I agree with the author's overall point: that attributes of men tend to have a higher spread, even when their average is similar to those of women. However I disagree with how he then applies this as a universal argument towards present and historical gender inequalities as well as using them as justifications for the inguinuity of men. He seems to mistake a social / evolutionary trend for an absolute argument as to why things are the way they are.

Take his discussion of academics, for example: (mainly focused on CS and biology, since those are what I know)

- Return for a moment to the Larry Summers issue about why there aren’t more female physics professors at Harvard. Maybe women can do math and science perfectly well but they just don’t like to. After all, most men don’t like math either! Of the small minority of people who do like math, there are probably more men than women.

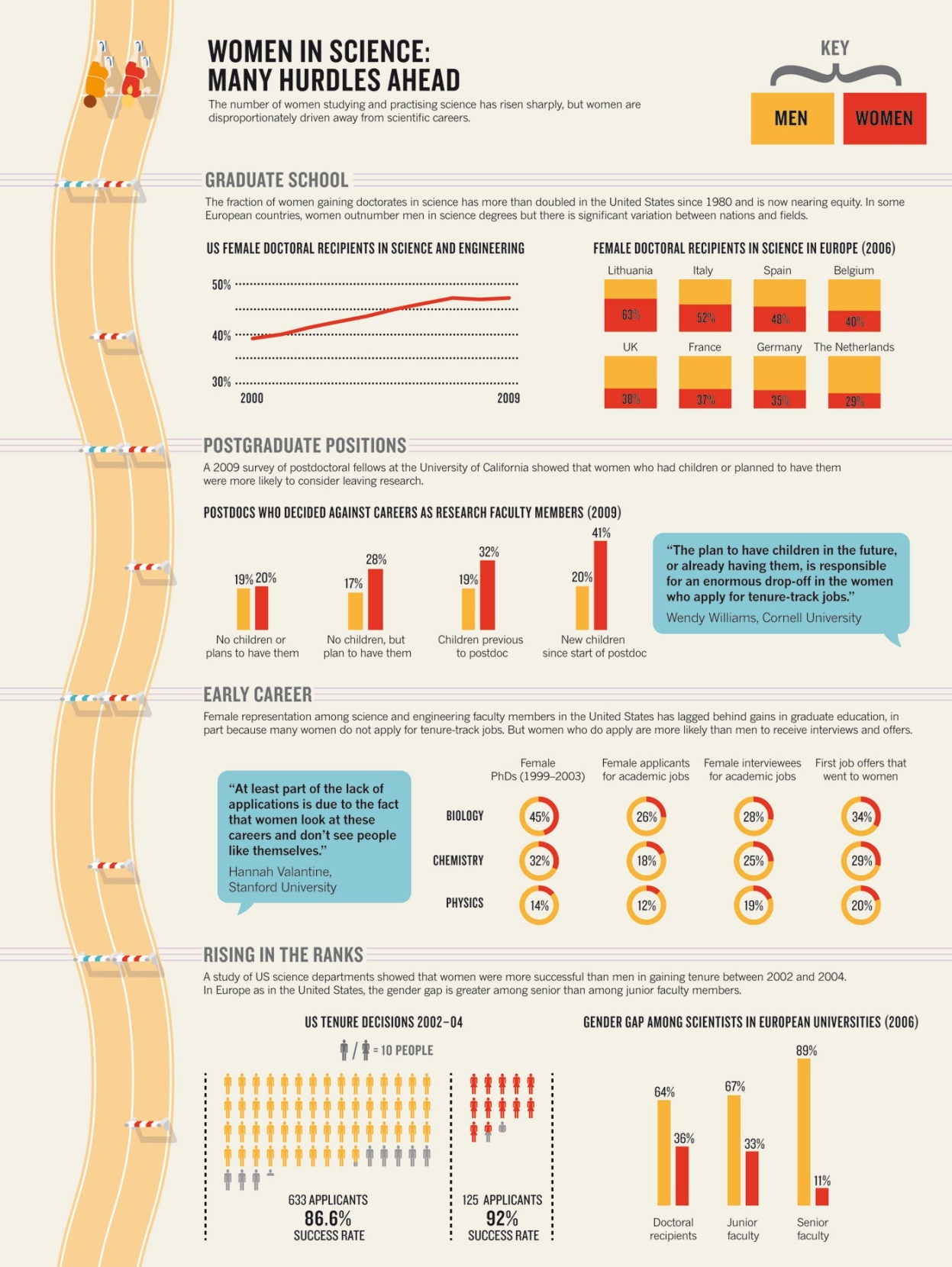

The thing is, gender inequality is itself not uniform across STEM. Across math, computing, and engineering, women make up a much smaller fraction of the students and faculty. Yet as you switch to biology, psychology, and medicine, suddenly the enrollment gap shrinks, blurs, and you switch from questions of sheer percent student composition to those of pay, faculty acceptances, and grant rewards.

Is biology a fundamentally less aggressive / testosterone-driven field? (Hint: no) Is biology a less social field? (Hint: no) Was computing more male-dominated from the start? (Hint: no) Or are these differences between these two fields due to cultural, historical, and behavioral differences that don't quite fit into the author's one-size-fits-all model?

There are definitely gendered differences in computing that are very tangible (see the general lack of female interest in bitcoin and cryptography), but they aren't really explained by the kurtosis of male attributes. Perhaps male dominance in those topics stems from a stereotypical desire to have complete control over ones digital information. Perhaps it's a self-perpetuating loop due to a historical lack of women there. But Ada Lovelace designed the first computer algorithm and Grace Hopper the first programming language. And the story there doesn't really match our authors' narrative:

- "Men were interested in building, the hardware," says Isaacson, "doing the circuits, figuring out the machinery. And women were very good mathematicians back then."

Isaacson says in the 1930s female math majors were fairly common — though mostly they went off to teach. But during World War II, these skilled women signed up to help with the war effort.

Bartik told a live audience at the Computer History Museum in 2008 that the job lacked prestige. The ENIAC wasn't working the day before its first demo. Bartik's team worked late into the night and got it working.

"They all went out to dinner at the announcement," she says. "We weren't invited and there we were. People never recognized, they never acted as though we knew what we were doing. I mean, we were in a lot of pictures."

At the time, though, media outlets didn't name the women in the pictures. After the war, Bartik and her team went on to work on the UNIVAC, one of the first major commercial computers.

--

Finally, I'd like to not let this paragraph go uncommented:

- But not very long ago, men were finally allowed to get involved, and the men were able to figure out ways to make childbirth safer for both mother and baby. Think of it: the most quintessentially female activity, and yet the men were able to improve on it in ways the women had not discovered for thousands and thousands of years.

Of all of the writing, this section bothered me the most. It's completely revisionist history that ignores the deliberate exclusion of women from the early days of medical research. Scientific medicine changed childbirth. Men led medicine at the time. Therefore only when men were allowed in could childbirth be improved. Garbage reasoning.

--

Still, appreciate the read, since it definitely got me thinking and I appreciate the author trying to broach this subject without being too PC-y or MRA-y about it. I don't like that he argues from such absolute terms, but bits of this is worth ruminating on.